Cryptodollars and the hierarchy of money

A simple, stablecoin, modification to Perry Mehrling's "Natural Hierarchy of Money"

Perry Mehrling offers an insightful analytical framework to study the different forms and functions of money. This model starts by offering a classification of different forms of money depending on their means of settlement, relationship with one another and their proximity to 'higher level money'.

In a hypothetical world with a gold standard, the structure could look something like the below:

Source: Perry Mehrling, Natural Hierarchy of Money

The distinction between 'money' (means of final settlement) and 'credit' (means of delaying final settlement) is a scale that varies depending on the instrument and the parties that are settling with one another. For normal people, bank deposits are a perfectly reasonable means of settlement even if they 'delay' settlement relative to a higher-level version of money. User behavior is the forcing function. Gold claims the highest position due to social convention that gold is valuable. Exchanging bank deposits is a reasonable settlement tool for normal people due to the social convention that bank deposits are assumed to be solvent. This simplified hierarchy is just an illustration, as in the real-world, even finer graduations are possible (e.g. securities like money market funds are closer to 'money' than long-term corporate bonds).

Our own Chef Sebastien gave a keynote at Stable Summit 2024 in Brussels, placing stablecoins firmly within the Natural Hierarchy of Money. This modification to the framework for the stablecoin era offers a helpful framework for understanding the role stablecoins play in the economy and how they can be useful instruments for settlement and monetary policy.

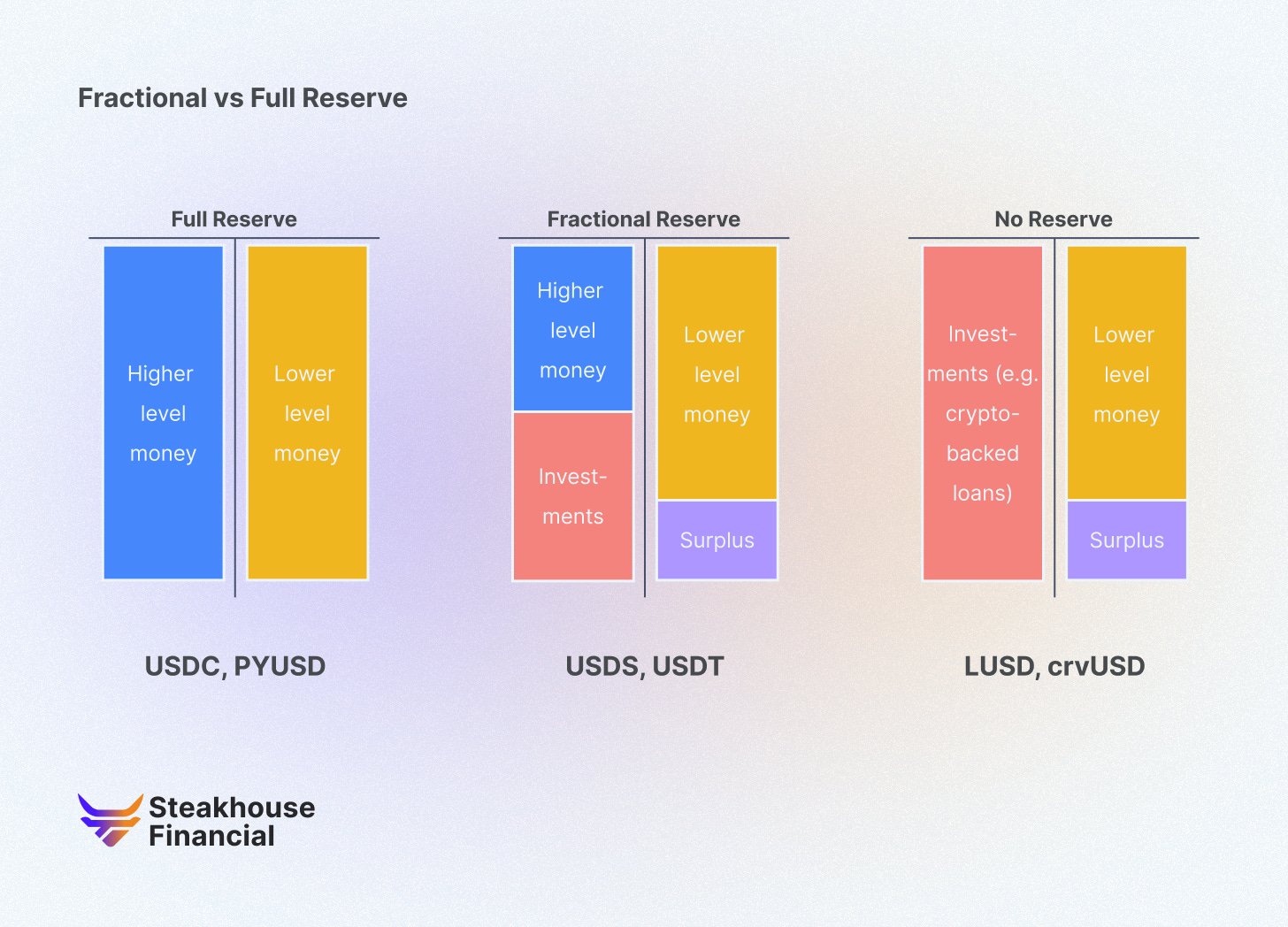

Stablecoins are a type of instrument that promise to maintain value relative to a reference asset. Cryptodollars are a subset of stablecoins that offer a path to redeem on-demand to higher-level forms of money, such as bank deposits. Within this framework, certain stablecoins could be classified further depending on the nature of their reserves.

Full reserve stablecoins are cryptodollars that offer the ability to redeem for higher-level money (e.g. USDC → USD bank deposits). Fractional reserve stablecoins are cryptodollars that offer the same redemption ability but also hold an asset composition with other investments that may be less liquid or riskier (e.g. USDS → USDC). No-reserve stablecoins would not be termed cryptodollars as they are not backed by any higher-level money (e.g. LUSD → ETH crypto-backed loan). N.b., so-called algorithmic stablecoins or endogenously collateralized stablecoins can simply be described as insolvent and disregarded (e.g. Terra).

In the stablecoin era, the hierarchy of money expands the 'bank deposit' line into cryptodollars. The highest level of money in the absence of a gold standard are central bank balances, which serves as the 'reference asset' in the stablecoin convention.

Stablecoins get a lot of attention from users and regulators around the 'peg', or the secondary market price. A novel feature of cryptodollars, relative to bank deposits, is that their market value fluctuates depending on user activity and often reflects fees charged to settle for higher-level money, as well as other perspectives such as the market perception of structural solvency or liquidity.

A crucial and often overlooked mechanism is the primary market, or the redemption path to higher-level money. Having a fast and liquid primary window ensures that secondary market price deviations can be arbitraged successfully by participants that have minting and redemption rights at the issuer.

Cryptodollars can experience very rapid inflows and outflows as a result of the speed of settlement of blockchains that they trade on. We measure gross outflows as the units of cryptodollars redeemed over a 30 day window as a percentage of the overall circulation, and net outflows after accounting for new issuance over the same period. What is evident from the data is that issuers of cryptodollars can process a very high volume of redemptions even when the net outflows are close to 0 (i.e. the circulating supply doesn't change much). For larger such cryptodollars, a 20% net outflow over 30 days would be considered quite a rare event.

'Singleness of money' allows, within a hierarchy of money, to move from one instrument to another frictionlessly. When a user transfers $10 from Bank of America to a friend's account at Citi, the settlement is abstracted and both deposits are fungible even if objectively they are exposed to completely different counterparties.

One of the difficulties that arises with the settlement between cryptodollars and bank deposits is that the settlement layers for each are mutually incompatible. Furthermore, banking regulators and banks themselves view stablecoins with suspicion, as instruments with the potential to usurp their market positions as deposit-holding institutions.

Some new stablecoins, such as M^0, stretch the possibilities of crypto-native mechanisms in a creative way and expand the definition of cryptodollars further. M^0 offers primary redemption directly from underlying treasury bills, bypassing full reserve stablecoins such as USDC or bank deposits altogether.

To preserve singleness of money in a world with stablecoins, a CBDC is not even strictly speaking required. Indeed, in many periods of history prior to the invention of central banking, privately issued liabilities traded at par with each other in different banking institutions. Although modern day intrabank settlement takes place within the central banking ledger, there is no strict technical reason why this ledger needs to continue being a COBOL mainframe last updated when the Soviet Union still existed.

However, competitive pressures between stablecoin issuers compounded with new stablecoin regulations may threaten to cement a lack of singleness of money within a hierarchy that includes cryptodollars. Even in a jurisdiction with clear guidelines for stablecoin issuance, such as the EU with MiCA, arguably makes matters worse for the prospect of a thriving stablecoin economy with singleness of money.

For one, MiCA obligates stablecoin issuers that seek singleness of money with the EUR (an E-Money Token, or EMT, approval) to hold a minimum balance of bank deposits in reserve, thus exposing the stablecoin to unnecessary counterparty risk. Furthermore, those reserves are considered 'flighty' in consideration of the rapid peaks of net outflows that stablecoin issuers may experience in volatile market periods. These liquidity requirements put an effective barrier between stablecoin issuers with respect to holding or recognizing each other's liabilities. This, in turn, slows volume clearing between stablecoins and enshrines a distinction between two stablecoins issued by two different issuers, even if both tokens were recognized as E-Money Tokens and therefore ostensibly legal tender.

Hopefully, with time, these regulations can take a more pragmatic view of stablecoins in light of their role in the hierarchy of money for users. The permissionless settlement rails that they work on offer significant advantages in terms of settlement risk, speed and finality. They also have no cap or throttle on the user’s ability to transfer significant amounts of balances from one party to another.

This could mean that, in time, the operating model for banks today may have to shift slightly and unbundle if users continue to increase usage of blockchain-settled cryptodollars. Ultimately, user behavior will, in practice, dictate (as it always has) what role in the hierarchy of money an instrument assumes.